Why We Need to Talk About Women

I have discovered that women’s history is a dangerous topic for me to research. I always come away feeling two things: rage over the way women have been treated over the millennia, and a heightened awareness of our own power and strength. If the latter feeling is what has been instilled in men after so many years of male focused history, I can no longer be surprised that, as a group, men are so cocksure of themselves.

But why is history so male focused? Women account for approximately 50% of everyone who has ever lived, so, presumably, they account for half of all history. Why don’t we talk about them more? Why is it the speaking in 1986, Gerda Lerner said:

When I started working on women’s history about 30 years ago, the field did not exist. People didn’t think that women had a history worth knowing.

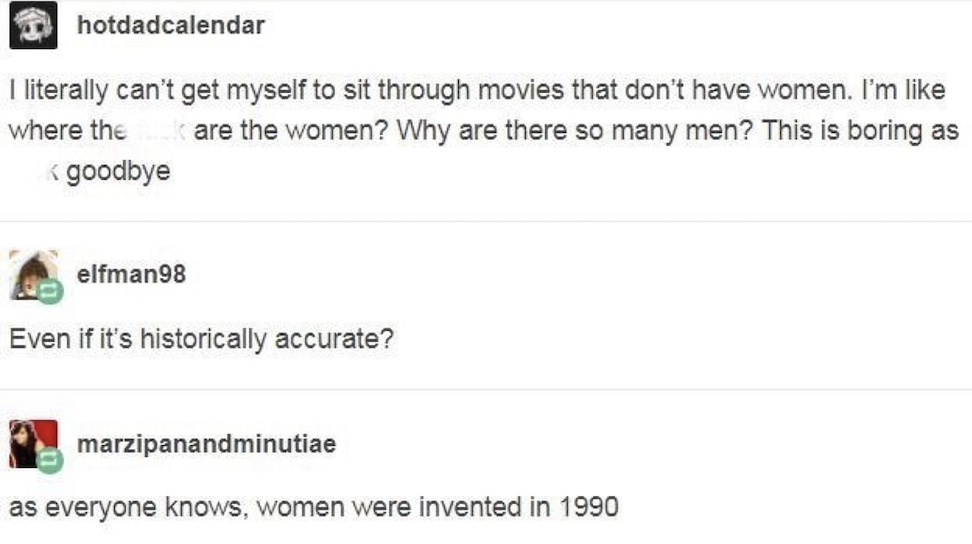

Why is it that the following exchange happened on Tumblr, a social media platform that was launched in 2007?

And why is it important for us to be correcting these misconceptions? Why is it essential that we begin to talk about and celebrate women’s history just as much as we do men’s history?

What is History?

At this point, I suspect it would be helpful to define what history is, so I am going to geek out about linguistics and etymology for a minute.

Google defines history as

The study of past events, particularly in human affairs

The whole series of past events connected with a particular person or thing

The Merriam-Webster Dictionary includes both these definitions, but the very first definition it lists reads “tale, story”.

The French language brings this connection between “history” and “story” into sharp focus, using the same word for both: “l’histoire”. All three of these words come from the Greek “historia”, which Wordsense.eu defines as:

Inquiry, examination, systemic observation, science

Body of knowledge obtained by systemic inquiry

Written account of such inquires, narratives, history

This word was then borrowed by Latin, where it meant “history, account, story”.

There is an intrinsic connection between stories and history. History is, in essence, the story, or narrative, that we tell about our past. Therefore, we must acknowledge that history faces the same limitations as stories do: limits of perspective and interpretation. This is especially important when considering the role of women in history.

Why Don’t We Talk about Women’s history?

Given that history is not a set record of things gone by, but an accumulation of stories about people, places, and events, our understanding and knowledge of history is influenced by factors such as who is doing the telling. Consider the proverb “history is written by the victor”. This does not specifically mean that only the winners of a given conflict can record their history, simply that the people with the power are more likely to be able to tell and retell their stories, which can mean their narrative is the prevalent one.

Unfortunately, throughout our past, it has tended to be men who had the power. Men were the ones who had access to the education needed to record stories and study the old ones. This means they were the ones who decided which stories were worth retelling, and how. They frequently decided that the stories of women were not worth being told.

This overlooking of women’s stories has led to the belief that women did not have stories, or histories, at all. For instance, in her book “How to be a Woman”, Caitlin Moran argues:

Even the most ardent feminist historians, male or female - citing the Amazons and tribal matriarchies and Cleopatra - can’t conceal that women have basically done fuck all for the last 100,000 years. Come on - let’s admit it. Let’s stop exhaustingly pretending that there is a parallel history of women being victorious and creative on an equal with men, that’s just been comprehensively covered up by The Man.

Here’s the thing about history though: you don’t need to be actively covering something up in order for it to be lost or distorted. You simply need to ignore it. Women’s history may not have been “comprehensively covered up by The Man”. Most of the time, it didn’t have to be. “The Man” was simply looking the other way.

Having said this, there are times throughout history when men have actively erased the contributions of women. Consider, for example, Rosalind Franklin. It was her work that led to the discovery of the double helix structure of DNA, but it was a group of men (Crick, Watson, and Wilkins) who took the credit, and the Nobel Prize, for it. As Nobel Prizes are not awarded posthumously, Franklin has never been, nor will she ever be, awarded for her work.

Consider also Pharaoh Hatshepsut. Daughter to Thutmose the First and wife to Thutmose the Second, Hatshepsut ruled in her own right for about twenty years, before she died and her step-son, Thutmose the Third, succeeded her. All the evidence suggests she was a successful ruler, but very little evidence remains as, during his reign, Thutmose the Third destroyed much of the evidence of her rule, including records, monuments and even some buildings. It was not until 1822 when the hieroglyphs on the walls of Deir el-Bahri were translated, that her name and story were restored to the historical canon.

Therefore, despite the fact that there hasn’t necessarily been a comprehensive cover-up of women’s history, there has been a tendency for men to ignore women, take credit for our achievements, or, in some cases, actively destroy evidence of our work and existence.

Why is women’s history important?

Given that history is the story of our past, it helps us to understand where we have come from, who we are, and what is important. This means that the histories we tell influence the ways in which we perceive the world around us. However, because women account for approximately half of humanity, a history that ignores their stories is an incomplete history.

According to Gerda Lerner:

Everything that explains the world has in fact explained a world in which men are at the centre of the human enterprise and women are at the margin “helping” them. Such a world does not exist – never has.

This exclusion of women and the resulting illusion of a world in which they are not vital contributors is problematic for both men and women.

For women, it teaches us that, as Myra Pollack Sadker says, we are worth less than the men around us. It undercuts our sense of power, autonomy, and significance. To claim, as Moran does, “that women have basically done fuck-all for the last 100, 000 years” erases not only the stories of individual leaders, artists, writers, and scientists, but also the stories of the communities of women who have tended fields, fed and clothed their families, cared for the sick and disabled, taught and raised children, and generally enabled society to keep functioning even under the most adverse of circumstances.

The over-emphasis on men’s history is both the result and cause of our tendency to dismiss the work of women. This can be seen today in everything from the general antipathy towards stay at home mothers to the open mocking of female artists and to the scorn of female-dominated workspaces, such as education and nursing. Notable examples of this in recent months include the absurd article by one particular male writer calling Dr. Jill Biden, First Lady of the USA, “kiddo”, and suggesting she drop her title of doctor. His argument was that because she was an Ed.D. not an M.D. she had no right to use it. I will not provide him with a further platform for his act of belittlement, but I highly recommend reading this article responding to his arguments. Another notable example was a recent joke at the expense of Taylor Swift, a female artist who has broken numerous records in the past 12 months alone.

This also affects people on a personal level. A woman who is taught that her work is not valuable learns that she herself is not valuable. She learns to hide herself away, just as the women before her have been hidden away, rather than stepping out to take her place in the world. Young girls are discouraged from pursuing sports, subjects, and careers that interest us, from being loud and brave and having fun. Instead of feeling able to embrace who we are, we are left to scrabble together some semblance of self and to defend it, all the while wondering if we should just fall in line and do as we are told. After all, a woman is not so important, is she?

This belief in the insignificance to women in comparison to men is not only absorbed by women. It is also absorbed by men. This is outright dangerous. A man who believes the women around him are worth less than he feels no remorse in stepping on them in the pursuit of his own goals. He believes that her obedience and submission to his will is his right, and he grows angry, frequently violent, when she does reject this belief. One needs only to consider the statistics on domestic violence to see this.

We also see this in Scott Morrison’s comments on the 16th of March, 2021 about the women protesting ongoing gendered violence and the Australian government’s lack of action regarding the prevalence of sexual assault within the workplace, including within parliament. “Not far from here, such marches, even now, are being met by bullets, but not here in this country,” he said, as though we should be grateful that our protest of violence against women was not met with more violence, as though that fact should somehow be enough for us. Mr. Prime Minister: that can not be where the bar is.

So these are the consequences of not talking about women and our history. But does talking about women’s history actually make a difference?

The answer, according to the National Women’s History Alliance, is yes.

Recognising the dignity and accomplishments of women in our own families and those from other backgrounds leads to higher self-esteem among girls and greater respect among boys and men. The results can be remarkable, from greater achievement by girls in school to less violence against women, and more stable and co-operative communities.

Speaking personally, every time I read about the accomplishments of women throughout history, or read a story that focuses on the power of women, I feel stronger and more capable. I feel less like I have to prove myself in a world that is unwilling to make space for me and more like I am simply existing in the space that is already mine. And I want all women and girls to feel that way. I want them to know our history and be aware of the strength and power inherent to being a woman that has been overlooked and belittled by a history and a world that over-values men.

Where can I learn about Women’s History?

It’s all well and good to talk about talking about women’s history, but where can we actually go to begin learning some? After all, the history books still preference men’s history and it’s a lot of work to find less mainstream resources. Well, fortunately, I have compiled a list of great resources. This list is not definitive by any means, nor is it as intersectional as I would like, but I myself am still learning and expanding my knowledge. This list makes a great starting point, and I have discovered that once you know where to look, it becomes easier to find more information

The Philosopher Queens, edited by Rebecca Buxton and Lisa Whiting

Forgotten Women, by Zing Tseng

Women to the Front, by Heather Sheard and Ruth Lee

Good Night Stories for Rebel Girls, by Elena Favilli and Francesca Cavallo

Who Cooked the Last Supper, by Rosalind Miles*

Pandora’s Jar, by Natalie Haynes

Rejected Princesses, by Jason Porath (rejectedprincesses.com)

*I have not yet read this book, but hope to soon. It’s been on my list for a couple of years.

Conclusion

History is, in essence, the stories we tell about the past. These stories help us to make sense of the world and ourselves. Unfortunately, in the telling of these stories, we have tended to overlook or minimize the stories of women. This results in a narrative of the world and our past that is incomplete and offers only a narrow understanding of the world. This is especially detrimental for women as they are perceived as being less important, both by themselves and by men. Talking about women’s history isn’t about reducing the history of men. It is about filling in more of the narrative and correcting an imbalance in our stories and understanding of the past. The goal is to better correct the ongoing political and social imbalances that exist between men and women around the world. We simply hope to restore women to our rightful place as the equal of men - their companions and partners in society, politics, and history.